Tout le devenir des marchés actions repose sur les GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Facebook...)

"Too often at the height of a bubble, liquidity is used as an explanation. This is voodoo strategy. Much of the ‘liquidity’ that supports markets at the height of a bubble is merely investors leveraging up on the back of long-established price momentum trades (often in cyclical risk assets). And even as the fundamentals deteriorate, investors keep borrowing and investing. But like Wile E. Coyote in the Road Runner cartoons, reality eventually catches up and the ocean of liquidity evaporates overnight until the next cycle. Poof!”

"Trop souvent au sommet d'une bulle, la liquidité est utilisée comme explication. Ceci est une stratégie vaudou. Une grande partie de la «liquidité» qui soutient les marchés au plus fort de la bulle n'est que des investisseurs qui s'appuient sur le dos de transactions de momentum des prix établies depuis longtemps (souvent dans des actifs à risque cyclique). Et même si les fondamentaux se détériorent, les investisseurs continuent d'emprunter et d'investir. Mais comme Wile E. Coyote dans les dessins animés Road Runner, la réalité finit par rattraper son retard et l'océan de liquidité s'évapore du jour au lendemain jusqu'au cycle suivant. Pouf!"

The Last Time Albert Edwards Saw "Nonsense" Like This Was 2008: This Is How It EndedAlbert Edwards admits he is "perplexed."

Writing in his latest Global Strategy report, the SocGen strategist admits that "until recently (ie the last few days), I had thought that the 35%+ rally in the S&P from its 23 March 2190 low would stall at around 2980 - the 62% Fibonacci Retracement level, as occurred in the previous two (2001 and 2008) bear markets. Hence, I was genuinely surprised to see the S&P climb above the technically important 2980 level, and yesterday power above its 200-day moving average."

Instead, the S&P is now less than 10% from February’s all-time high, and with the US unemployment rate heading towards 20%, Edwards asks rhetorically: "At what point does the stark disconnect between Wall Street and Main Street become a political embarrassment for the Fed? Maybe never."

Maybe never, but most likely soon: as Bank of America's Michael Hartnett wrote last Friday, the absolute limit of bear market rallies in 1929, 1938, 1974 was a 61% rebound from lows (after an avg 49% drop), which would take the S&P500 to 3180 this rally, so another 120 points which at this rate means another 3-4 days of gains.

Edwards does not look that far back, however, and instead he reminds is that the rally from the March lows is similar to last year’s rally, which similarly was narrowly concentrated on the large cap ‘growth’ stocks aka the FAANGs (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and the stocks formerly known as Google, but now called Alphabet).

And while the bearish strategist offers a mea culpa, saying "I have been very wrong as I had expected to see a collapse in the FAANG stocks and ‘tech’ generally, as the recession exposed large parts of the tech universe as cyclical stocks masquerading as ‘growth’ stocks, ... but how wrong I was, as the stay-at-home nature of this coronavirus-induced recession has instead given the FAANG and tech stocks a whole new impetus", he advises his clients that he, too, has been here before, in the first half of 2008 to be specific.

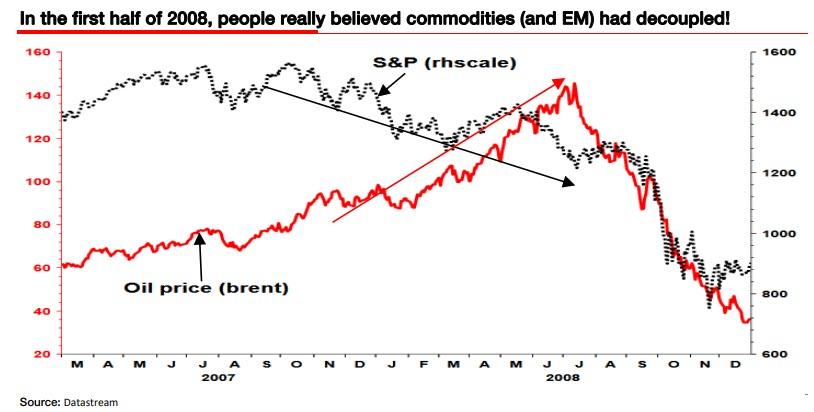

Cast your minds back. The S&P had topped out in October 2007 - the bear market had begun and the US economy had slipped into recession. Do you remember the mantra that emerging markets had de-coupled from the global downturn and commodities would remain resilient as a result? Do you remember the touting of ‘BRIC’ EM investing? So, for most of H1 2008, commodity prices soared.

At the time Albert said this talk of de-coupling was nonsense, and is "what behaviourists call a bubble of belief as Fed liquidity had funnelled into this asset class as a last refuge from the cyclical meltdown."

Fast forward to today when Edwards saying the current decoupling of tech/growth/momentum, or generally - the FAANG rally - too "will end in collapse in the same way EM and oil did in H2 2008. Indeed, the title and first paragraph above are taken directly from my weekly of 5 March 2008 with FAANG replacing commodities and EM." And just to make his point, we notes that his lead in sentence was taken directly from his weekly of 5 March 2008 with FAANG replacing commodities and EM.

I have a high conviction that before the end of this year the

EMsFAANGs will be unravelling, as the structural arguments supporting these bubbles turn to cyclical sand.For those who prefer visual reminders, this is what the S&P did for the 6 months after the recession of 2007 had started:

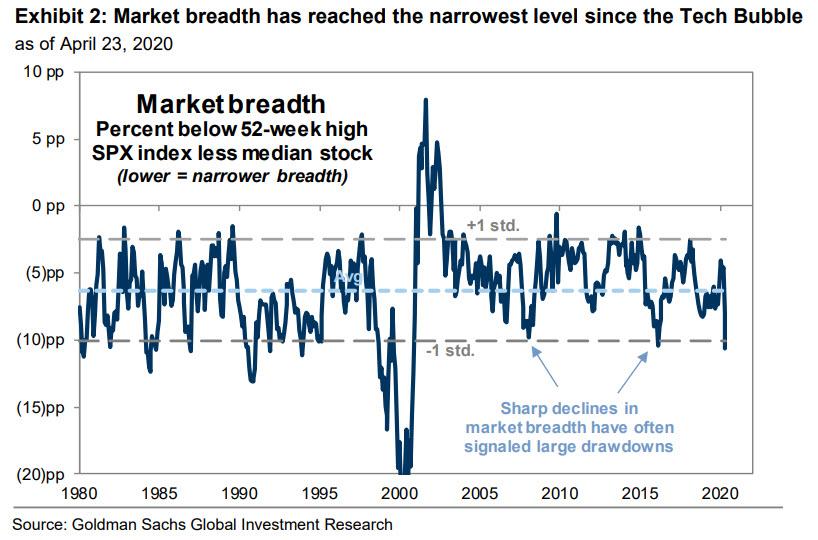

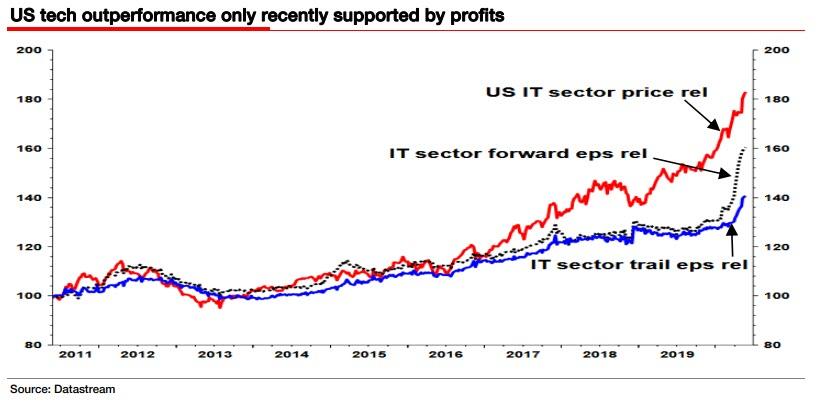

Shifting to the here and now, Edwards then writes that in the run-up to the current recession, "US tech price outperformance far outstripped relative EPS performance." As the SocGen strategist elaborates, "I felt this was yet another Fed inspired, liquidity driven bubble that would burst in the coming recession - like the late 1990s Nasdaq bubble." It's not just him though: even Goldman recently warned that the FAAMGs have gone far too far, and a moment of reckoing is coming as a result of the record concentration in just a handful of stocks as market breadth has plunged to near all time lows.

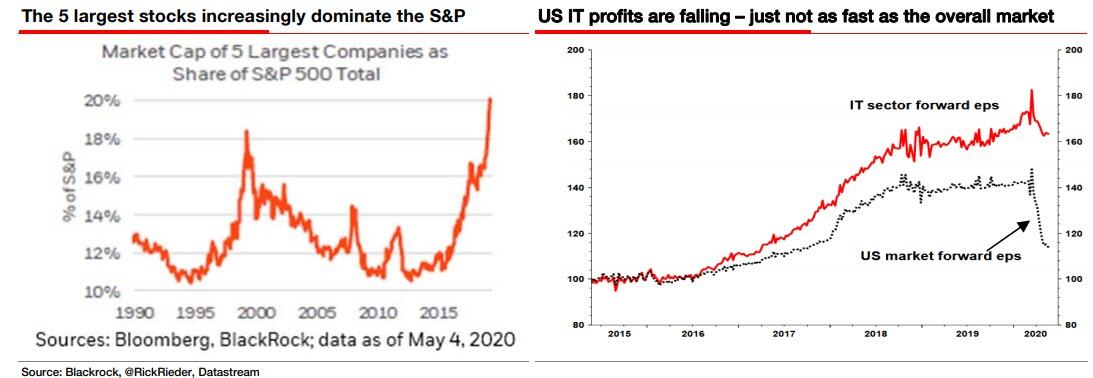

However, what both Goldman's David Kostin and Albert Edwards missed, is that the unusual stay-at-home nature of this coronavirus-driven recession has boosted IT and media related expenditures generally in a way that could not have been anticipated. Interestingly, US tech sector profits have only really outperformed decisively in the past few months (see chart

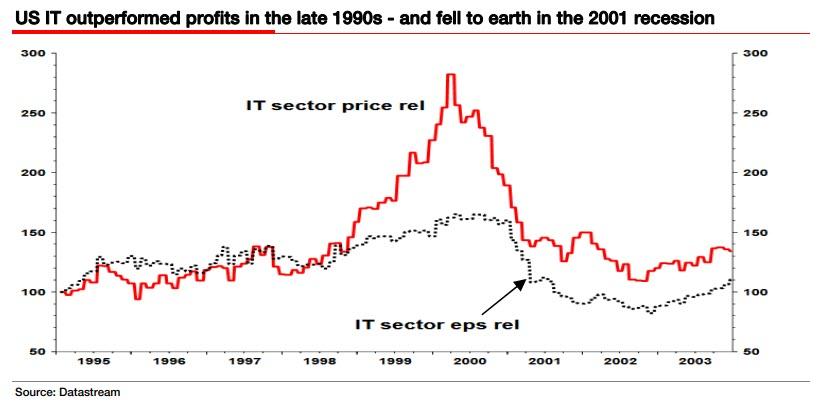

below), but rather than profits merely catching up with previous heady price outperformance, IT stocks have continued to surge higher relative to the market, especially in the rally since March.This is not the first time we have seen this pattern: in the late 1990s, Edwards writes, tech stocks also enjoyed a period of massive outperformance that had hugely outstripped what was also a moderate outperformance of their EPS relative to the market (see chart below), "and just like recent times, what propelled US tech valuations to stratospherically high valuations back then was ample Fed liquidity and a bubble of belief."

Then the 2001 recession hit, and many tech stocks suffered a "totally unexpected" fall in profits. These were not growth stocks at all and shouldn't have been on 40x+ PEs. "These were in reality cyclical stocks trading on peak multiples on peak cyclical earnings when they should have been trading on top of the cycle, single-digit PEs" Edwards booms, but of course it is easier to make such observations in retrospect when the frenzy is long gone. Of course, when the market "discovered" these stocks were on the wrong PE ratings based on the wrong forward earnings, the Nasdaq bubble collapsed. And even the true growth tech stocks collapsed in price as all around them earnings bombs were exploding. At that point, "investors rushed for the hills throwing their true growth tech babies out with the bathwater", gloomy Albert concludes.

Yet it may (not) come as a surprise that Edwards is even gloomier now, even though as he admits, "his expectation of a similar fate for tech in this recession has been proved wholly wrong. To be honest, I have been left scratching my head. I feel I am suffering from that awful psychological affliction virtually unknown on the sell-side - namely self-doubt!"

For if the large-cap US indices are increasingly dominated by growth sectors such as IT, or specifically the FAANGs (see left-hand chart below), that typically benefit when bond yields fall (and I expect the US 10Y bond yield to fall to -1%), why can'’t the S&P carry on rising in line with falling bond yield? Maybe ever higher PEs are consistent with low bond yields after all if the market is stuffed full of growth sector bond proxies?

This, of course, is taking the Fed model to its ludicrous extreme, one where negative rates would in theory at least, presuppose infinite stock prices. After all if discounting future cash flows using negative discount rates, prices rapidly approach +∞.

Edwards had considered this possibility last year in the run-up to this recession, and while he thought quality stocks (with sound balance sheets) and defensive sectors would continue to re-rate higher with falling bond yields, the IT collapse would surely help lay the overall market low - this is a rehash of Goldman's bearish April thesis. For even with soaring stay-at-home expenditures on IT, profits for the tech sector have actually fallen. But something was different: unlike 2001, the decline is at a much slower rate than the overall market (see righthand chart below).

Putting it together, Edwards says that we have now reached a permanent market and profit divergence, where the FAANGs specifically, and IT and growth stocks generally, have continued to outperform the market, taking PE valuations to extremes not seen for many a year; which makes sense: after all it is the small, soon to be insolvent "value" companies that trade at a depressed multiples, and as they fail and are removed from the S&P, multiples will only rise. But here a thought: keep in mind that the FAAMGs are for the most part ad-revenue driven. In a world where just the 5 tech megacaps survive (enabling market multiples to approach 30x) and where most small and medium business have collapsed, who will need, or pay for advertising? What will be the FAAMGs business model after the coming tsunami of defaults has wiped out trillions in ad spending? Just a thought to keep in mind as everyone rushes into tech names.

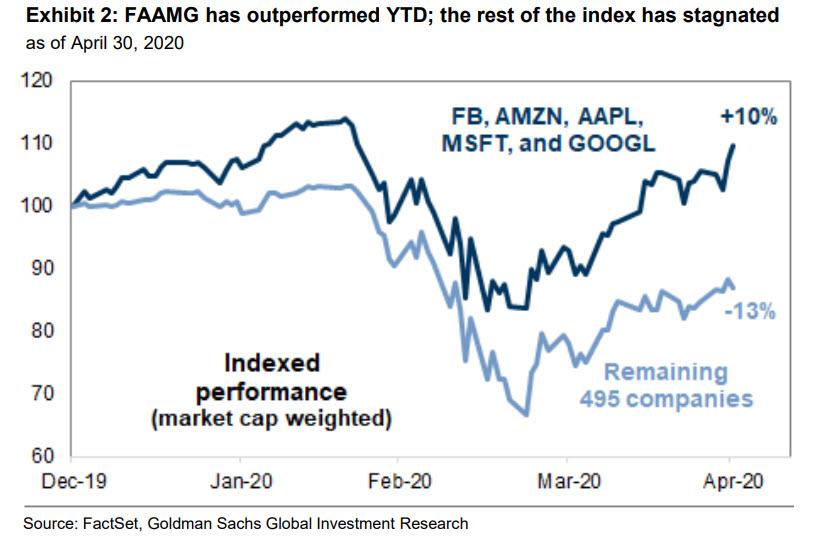

And while everything contemplates this dilemma, Edwards takes us back to a topic familiar to most, namely the massive outperformance of just a handful of stocks vs everyone else, something we discussed most recently in "The FAAMGs Are Up 10% In 2020; The Remaining 495 S&P Stocks Are Down 13%."

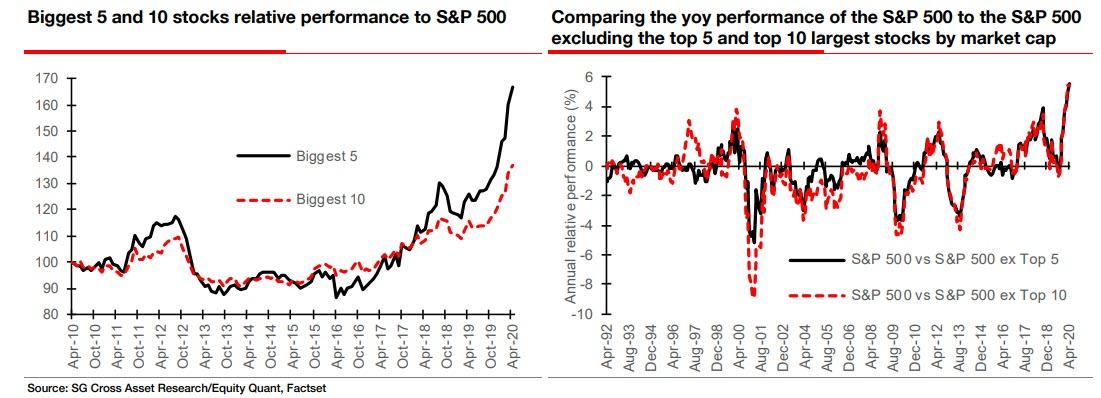

Edwards here reminds us that earlier this year, just before the market peaked in February, SocGen's quant Andrew Lapthorne, published the charts below showing how the largest cap stocks in the US had outperformed the overall market so comprehensively over the last three years - only.

The word only is a very important caveat and emphasises just how unusual this period of market domination by a small number of stocks really is (the top 5 being the FAANGs). We have been here before with investment fashions like the BRICs, the nifty-50 or indeed the famous five (maybe they weren'’t an investment theme after all, but why let the facts spoil a good acronym!).

Alas, for every such period of massive outperformance by a handful of stocks, the detox is especially painful, and Lapthorne notes that "history shows that periods of extreme outperformance by the 5 or 10 largest cap stocks are eventually counterbalanced by periods of huge underperformance when bear markets occur" (right-hand chart above). In fact, over the long term Andrew noted that the ten biggest stocks have lagged the market by 150bp per annum on average since 1990, while the top five stocks lost 100bp per annum vs the benchmark link.

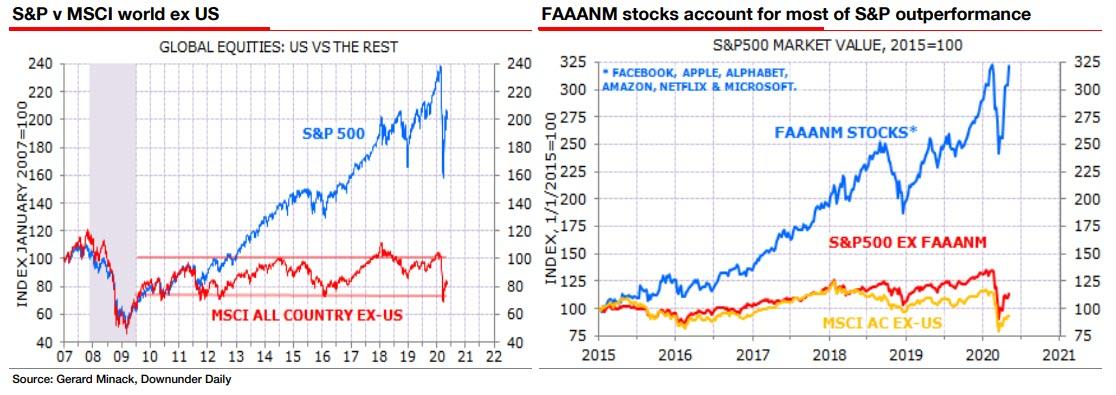

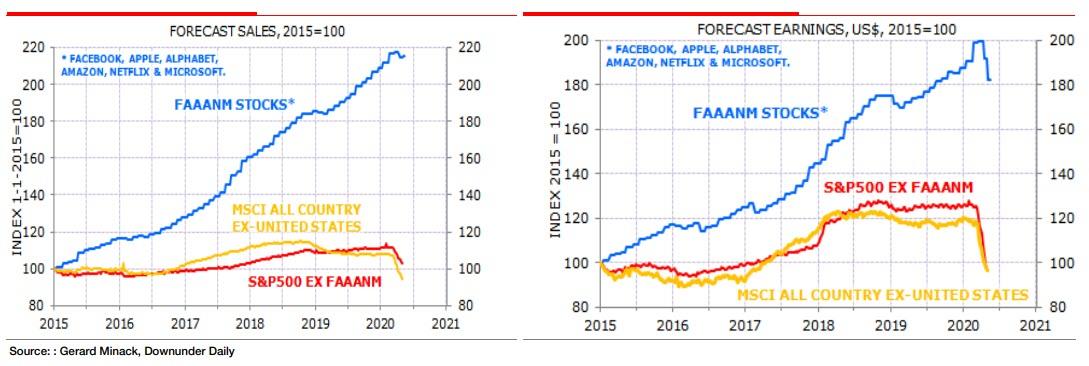

Albert concludes by expanding on this topic of super concentration, and using a concept spawned by Gerard Minack, author of the Downunder Daily, namely adding Microsoft to the FAANGs (calling Google by its correct name Alphabet) to form the

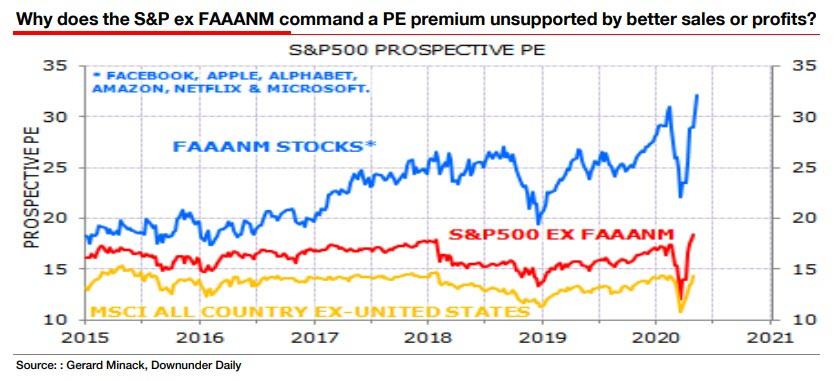

FAAANMs (Facebook, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Netflix & Microsoft), Gerard and Edwards highlight that the massive outperformance of the S&P versus the MSCI rest of the world (RoW) is almost entirely attributable to the FAAANM, top 6 stocks. The S&P494 ex FAAANM, is almost as dull as the RoW. "This is significant as it is shocking" in the words of everyone's favorite permabear.Extending this analysis to fundamentals reveals the same pattern: as Edwards puts it, "the pedestrian price performance of the S&P 494 (ie S&P 500 removing the FAAANM stocks) in line with the RoW stock markets is entirely in line with both their sales and profits performance. Remove the FAAANM stocks and profits are back to 2015 levels."

Echoing Goldman's April note, Albert exclaims that "it is shocking quite how reliant the US equity market has become on just six mega-cap stocks because it emphasizes the risks if, for any reason the bubble in the FAAANM stocks burst as I believe it surely will. Indeed, as Andrew showed earlier, history supports that view."

So how do these massive divergences resolve themselves? One, arguably the simplest way, would be for bond yields to keep rising, value stocks to surge, and growth names to plunge. But Edwards expect bond yields to first fall further (before exploding higher).

Instead the SocGen strategist believes that what is really going on, is that profits in the FAAANM stocks are falling (above right chart) in line with the chart shown earlier of forward EPS in IT falling (intuitively this makes sense because as the economic recession gets worse once stimulus payments fade, ad spending will plunge, as will ad revenues for the FAAMGs.

Edwards concludes by repeating what he said two months ago, namely that "this recession will ultimately expose these and the tech sector to be far more cyclical than appreciated. And it will be difficult in that environment to maintain their 32x forward PE (see chart below)."

Furthermore, echoing Minack, the SocGen analyst writes that "it is curious why the S&P494 enjoys a superior rating compared to the RoW when its sales and profits are no better than the RoW. History suggests there is no justification for this and it is part of the bubble of belief driven by Fed liquidity. "

In conclusion, and going back to the "tsunami of liquidity" theme that made this all possible, Edwards ends where he started with a quote from his Global Strategy Weekly from 2008 when the market thought EM and commodities had decoupled from the RoW. This is what he said on 5 June 2008,

"Too often at the height of a bubble, liquidity is used as an explanation. This is voodoo strategy. Much of the ‘liquidity’ that supports markets at the height of a bubble is merely investors leveraging up on the back of long-established price momentum trades (often in cyclical risk assets). And even as the fundamentals deteriorate, investors keep borrowing and investing. But like Wile E. Coyote in the Road Runner cartoons, reality eventually catches up and the ocean of liquidity evaporates overnight until the next cycle. Poof!”

Commentaires